The Switch-Part 2

The second day he is sick we teach body parts. Furaha speaks Swahili, translates my English dialogue. Then I point to each bit of anatomy - Elbow, Knee, Neck, Foot - and pronounce it for the children in English. Furaha slaps the blackboard with her switch, and the kids sit up with straight backs and call back the English in little animal voices. We go to Furaha's house during recess, and I bring milk for her chai. She thanks me, and then she gives it all to me. I say No, that's not what I wanted, it is for you, and she shakes her head and hands me my cup.

The third day we sing songs in the morning, and Furaha has me teach the kids songs in English. On the spot, I cannot remember any songs, suddenly I have never before heard any songs. And then I remember, all those little expectant brown faces staring at me, I remember The Itsy Bitsy Spider. I start to sing it, to teach it to them, and then the kids are singing too. They already know it. I don't remember teaching them, and I don't remember Max teaching them, and then I hear Furaha: You are not the first Miss Mzungu and you will not be the last. I keep singing, keeping my head up like the kids that first day, and I feel hollow and so not special. My father used to hold my chin and look me square in the eye and tell me I am special, tell me I will do big things, one day. I am not special, but I finish singing the Itsy Bitsy Spider, and so do the children, for they know it as well as I do.

At recess, Furaha buys hot, oily mandazi, and I buy her a chocolate bar and we eat them sitting on the teacher's desk at the front of the classroom. We cross our legs Indian-style and she asks me if I want to be a teacher when I am older. I already feel pretty old, but I also feel like I should be wearing a red uniform and learning to sing songs.

"I'm not sure," I say, chewing.

"Don't do it."

"Why?"

It is hard. I am a teacher and then I have to act like my students' parent and then you wazungu come and I am your teacher and I have to act like your parent and it is just not very nice.

"Do something else," I offer.

"I can't do anything else. I am very lucky to be this. I love it."

"But you just told me not to do it."

"Yes. You are a mzungu, Danica. You can be many things."

The fourth day, we review body parts, and then we draw pictures of our houses. Furaha draws hers on the board in colored sidewalk chalk, and I notice that she adds a solid wooden door, instead of the kanga that blows in the wind. The kids draw theirs, with their family lined up outside, all spindly legs and no necks.

"Yo' house, Mees Danna?" asks one of the little girls, Maua.

"Yo' house! Yo' house!" the children chant until Miss Furaha snaps the switch against a desk at the front of the room.

"Go ahead and draw your house, Miss Danica," Furaha says, handing me the sidewalk chalk. She says my name. Her eyes are a dare. I take the chalk, and I draw a lie.

My father recently built a new wing on our house. He added a second guest room and a cinema where he does showings of documentaries on clean water and the shrinking habitat of polar bears in the arctic. I cut off the new wing. I draw grass where the swimming pool is. I slice the top floor off, and I picture my bedroom with its vintage white vanity collapsing and blowing away. I draw a neat rectangle with a pointed roof, two square windows and one door. I draw a tree next to it, with a cloudlike mass of leaves on top. I draw my mother, and my father, and me, all holding hands out front.

Furaha smiles at me.

"Ooh! Pendeza!" says Maua.M

"Yes, teachah, pendeza!"

"Pendeza in English?" shouts Furhaha. There is silence.

"Dog?" asks Iddi.

"Dog?" Furhaha mimics, indignant. "Not dog!"

"Not dog?" asks Iddi.

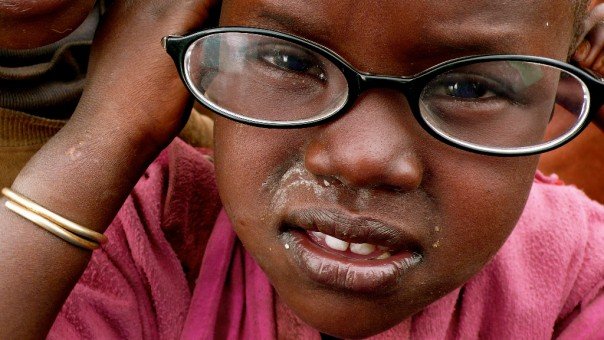

"Iddi, sema pendeza ni kiingereza," Iddi, say pendeza in English. Iddi shakes a little, and he starts to smile awkwardly, showing the rotting bits on his two front teeth. He sticks his finger in his mouth and he looks at me, and his eyes are almost crying already. He does not look at Furaha, he looks just at me.

"Iddi! Sema!" Iddi! Say something!

"Boy? Cat? Dog?"

Furaha is across the room and Iddi is still looking at me, but then his eyes are closed and Furaha's stick is coming down hard on his back, and the sound bites my ears and Iddi starts to cry, a wailing like a small baby. Some kids laugh, holding their small hands over their mouths, and then Furaha is laughing too. Laughing hard, and tears are tumbling down her face and they are tumbling down Iddi's face too and still the switch comes down and gnashes at his back.

I hear something, over the crying and the laughter, and I turn to Maua, who has her eyes closed tight and she is saying, "Beautiful. Pendeza ni beautiful. Beautiful! It is beautiful!"

Then I am across the room like Furaha was, and I am holding Iddi like a baby, and his head rests in the crook of my neck. I push my way through the desks, Iddi's dusty black shoes banging against the wood. Furaha laughs more, and I turn and I look at her and she is laughing and there are tears down to her chin and she looks at me and says, "GO."

The fifth day, Furaha does not come. Joseph drops me in front of the school, and it is just me and the children. I teach them math. They call it Arithmetic, so I do too.

"Today, we are going to learn arithmetic!"

They look at me, and then one boy, Musa stands on his desk and shouts something. Then the kids laugh and they all start shouting. Musa sings something, and then they are all singing and standing on their desks, spinning like they are in a centrifuge, and I am left standing still.

"Quiet." I say, knocking my knuckles on the blackboard. It is still loud.

"Quiet!" I shout, like Furaha. Some of the girls sit with their hands folded in their laps, but the classroom has devolved into something chaotic, and I feel my eyes needle at the corners.

"Kimya! Quiet!" I shout louder, and it is quiet for a moment. "Kaa!" Sit! Some sit, but half are still dancing and whooping. Juma, a short boy with a freshly shaved head jumps from one desk to the other. This looks fun, so a few others follow suit.

"Kaa!" I shout again, and Juma sits neatly on the cement floor. I want to tell him to sit in his seat but I don't know how. "Kaa in seat!" I yell.

Another boy jumps, a boy whose name I don't know. I am ready to yell again, but then he misses. He misses the desk he is jumping to, and he snaps his mouth against the rubbed wood. He is bleeding and it is pooling on the cement, a Rorschach test in crimson. He is screaming, a primal screaming that rouses mothers from their sleep, that stings something inside, something I don't know the name for. I pick up the nameless boy, and I hitch him up against my hip. He is screaming in my ear, strings of pink saliva stretched taught between his teeth. I don't know where to go, but I do know where to go. I run to Furaha's house. The boy whose name I do not know, his blood is saturating the shoulder of my blouse, and I try to run as gently as I can around turkeys and cooking fires.

Furaha's house looks like the one on the chalkboard yesterday, and I bang on the wood next to the not-door.

"Furaha!"

"Kwa?" She asks, ripping back the kanga. What?

"Help, Furaha, I need you!"

"You don't need me. You know what to do, right, Miss Mzungu?"

"Just help me, Furaha."

She lines her couch in greasy newspaper and lays the nameless boy on it.

"I am not a doctor," she says, turning around to look me in the eye.

"I know," I say.

"Then why do you bring him here?"

"You're the only one I know."

"You know other people."

"I trust you."

"You don't like me, Miss Mzungu."

"I trust you," I repeat.

Furaha peels back the boy's lower lip. She wipes it with a damp cloth, and she laughs. Always laughing.

"The boy is fine," she says, "come closer." I come closer, and the boy is looking back and forth between us with wide eyes. I look in his mouth, and Furaha points to a small cut. It bleeding, but she has wiped the blood away. The boy's teeth are unscathed, and the cut is shallow.

I look at Furaha.

"Thank you."

"What for? I didn't do anything."

"Just thank you, for helping me."

"It is not my pleasure, but you are welcome." Furaha says, smiling a little. I laugh. I sit on her floor against the couch.

"I thought I broke him."

"Broke what?"

"Broke him," I say.

It is Easter and there is no school on Monday. We do not celebrate Jesus' resurrection. We go to the Serengeti, Max and me and some other volunteers. We are glad there is no school and we are glad Max has no more amoeba, and on Easter we are glad as we are supposed to be. We see giraffes and we see a baby elephant with its feet like kettleballs and we sit around a fire in the savannah and tell stories of white people eaten for dinner by lions. If not lions, then hyenas. After Easter Max comes back and Furaha and I do not know how to act. With him or with each other. We go back to the way we are, and she doesn't say my name anymore. We are Mister and Miss Mzungu, Max and I are. Max does the math lessons and I do the English ones. Furaha sits at the teacher's desk and strokes her switch.

Furaha stops coming back after recess. She takes her tea at home and she does not invite me and she does not invite Max, so we play with the children outside. I lean against the blue cinderblock wall, under the six inches of shade afforded by overhang of the roof. Max plays soccer with the kids, and little Musa hangs from his cargo shorts trying to get the ball from him. Max is sweaty, and his shirt drapes over him like it is made of liquid, frozen in the moment of pouring. I am coughing on dust, and when I open my mouth it plastered to my teeth, so I wipe the grit against the inside of my upper lip. The girls are tugging at my ponytail, so I release it - – Rapunzel, Rapunzel, let down your hair! - and let Maua and Aisha braid it with their slippery fingers. It does not become a braid, but rather a massive oblong tangle. I shake them off once I realize the extent of the damage and they laugh.

"Beautiful," Maua says decisively, slipping her hand into mine.

That afternoon we let the children color. Max is hot and I am hot and we do not have it in us to teach. No arithmetic and no letters, no elephants and no lions. Just coloring. Iddi asks us what they are supposed to be coloring, and it takes a few tries for Max and me to understand. I feel guilty, not even speaking their language but being left in charge of their education.

"Anything," I say. I do not know the word in Swahili, so I look it up in my phrasebook. "Chochote."

Max sits down at the teacher's desk and says, "Only an hour to the van."

The kids color for a half hour and then they get restless. They start to kick the chair of the child in front of them and Musa begins to lead the class in song again, like the day the nameless boy fell. Max looks up through heavily lidded eyes and shushes them.

"Angalia," says Juma. Look. And he stands from his desk. He looks at me; he looks me in the eye just the way Furaha does. Like he is daring me. He walks carefully (like he is on a tightrope, one foot aligned with the other) to the teacher's desk, and he slams his hand on it – Slap – and runs back to his desk. He sits quietly. I glare at him.

"Kaa." Sit.

"I am sit." He says, in English. I shake my head.

"Stay sitting, or you will stand in the corner." Juma looks at me. He stands. He walks toward the teacher's desk. I lift him by the wrist and plant him in the corner, facing the wall. "Stay." I say.

Juma sticks his tongue out at me. He shakes his backside for the students, like a hula dancer, wagging it and making them laugh.

"Juma!" I shout.

"Calm down," says Max, "he's just having fun."

"But he isn't listening to me!"

"He's just a kid."

"He isn't like this with Furaha!"

"I wonder why," Max says, snorting.

Juma pinches me, just a little pinch, a playground pinch, a pinch-me-so-I-can-believe-this-is-realpinch. I grab Juma's wrist and he looks up at me, his eyes alert and awake and scared. I don't look at Max first. I just slap Juma.

I slap him once, on the forearm, and it makes a sound that bounces around the walls of the room like a song, and it stings my hand and Juma rips his arm from my hand and rubs it quickly, making a shh shh shh sound.

"What did you do?" Max asks, jumping up.

"He pinched me!" I say, flushing. I feel my chest marbleize red and I look at the ground.

"But you hit him!"

"Furaha does it!"

"You don't want to be Furaha, Dan!" He says, grabbing my shoulders.

"She can control them!"

"Look, Danica," Max points at Juma who has jumped onto Maua's desk and is sticking his tongue out at me, "You aren't Furaha. You can't scare him."

I rub my hand.

"What?" Max asks.

"My hand hurts," I say, "I hurt myself."

Mary Schaller graduated in 2006 from Cape Cod Academy, then spent a "gap year" volunteering both in a Guatemalan orphanage, and a school in Tanzania. She is a recent recipient of a BA in International Development from McGill University in Montreal.

Mary won First Place for the Chester Macnaghten prize in Creative Writing, awarded by McGill University for The Switch -this story is fiction, based on her real life experiences in Tanzania.

Mary lives with her sister in Seattle, WA, as she pursues a career with refugees while continuing to embrace her love of writing--and often visits her parents in the Web Princess palace.

|